Philosophers on Film: Strawson and Evans Chat

Zed brought this to my attention. I will look this up next time I'm in Oggsford.

There is also a video recording of Evans and Strawson discussing the nature of truth.

Zed brought this to my attention. I will look this up next time I'm in Oggsford.

There is also a video recording of Evans and Strawson discussing the nature of truth.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

12/30/2006

0

comments

![]()

On November 1st, the workshop met in Cobb 103 to discuss David Velleman's paper, "Self to Self".

PART I

Jason introduced the paper by pointing out how Velleman distinguishes the psychological sense of self from the metaphysical sense of personal identity. Velleman is concerned with conditions of selfhood through time. Roughly, what makes a future or a past self mine is my ability to anticipate certain experiences or have certain intentions or memories without needing to identify whose experiences, intentions, or memories they are. That ability is distinguished from the activity of imaginitive identification with someone else, e.g. Napoleon.

I can imagine that I am Napoleon by imagining certain experiences as being had by Napoleon from a first-personal point of view: how the smoke and noise of Austerlitz must have seemed to him, for example. This kind of imaginitive identification requires imagining having his experiences first-personally. But in so doing, I have to additionally think of these experiences as being had by Napoleon. My imagining that I am Napoleon would therefore involve thoughts of the following kind:

I see that the allied center is weak.

I am going to ask Marshal Soult how long it will take the troops to reach the Pratzen Heights.

I am ordering the attack on the Austrian & Russian forces.

"I" here refers to Napoleon.

The final thought ("I" here refers to Napoleon) is what distinguishes "imagined seeing" from memory or anticipation, which are more intimate relations I have to my own selves. What accounts for the special kind of relation we have to memories or anticipated experiences or intentions that is missing in the case of mere imaginings? It is some kind of (special?) causal relationship:

"I don't have to specify a person from whose point of view I am trying to frame my intention, because the future point of view is fixed by the future causal history of the intention itself" (71).

"I do not center the memory on any past subject--it is just presented to me as having been copied from a visual impression, and it consequently represents things as seen by the subject of the impression from which it was, in fact, copied. Who he was is then determined by the image's causal history" (59-60).

Velleman thinks that with the distinction between self and personal identity in place, he can make better sense of what we are interested in in splitting cases. We care about being able to anticipate experiences and frame intentions without having to have the additional thought that the self having the experiences is, e.g., David Velleman. If I know that my brain is going to be split and implanted in two different bodies, I can't anticipate experiences without also specifying which of the recipients is going to have the experience, the thought goes.

PART II: Discussion was wide-ranging. The following is a small selection of the topics we covered:

1. Jason asked whether it's correct to say that a memory "purports to be a copy of a visual impression". What does this copy purport amount to? Is it part of the content of the memory? It seems that usually, I can just remember an event, or an object, without there being any sense that my memory is a "copy" of a visual impression.

2. It struck the workshop as odd that Velleman is happy to say that given a suitable causal history, I can have Napoleon's memories in the same sense in which I can have my own, as presented to me as being mine without any additional thought of identification. So, for example, if Napoleon's memories were somehow transferred to me, it would be true to say that I remember being at Austerlitz and giving the order to attack the Allied forces. [Would this be any consolation to Rachel, the replicant in Bladerunner who finds out that her childhood memories are implants, supplied by the niece of the person who programmed her? It seems that Deckard, equipped with Velleman's account of selfhood, could say that those memories are Rachel's, even though the experiences that are their source were had by a different person.]

3. I asked about Velleman's account of intention. Velleman says "I don't have to specify a person from whose point of view I am trying to frame my intention, because the future point of view is fixed by the future causal history of the intention itself" (71). But what about a surprise splitting case, where on November 29th I frame an intention to write and drop off a check at the housing office tomorrow, but while I'm sleeping, my brain is split and implanted in two different bodies. The intention survives the split, and on November 30th, both recipients of my brain halves write a check and drop it off at the housing office. If the future point of view is fixed by the causal history of the intention, then which of these two points of view was the one that I had in mind in framing my intention? It doesn't look as if there is an obvious answer to that question. So it appears that the "future causal history" of the intention is not enough to fix the person from whose future point of view the intention will be carried out.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

11/29/2006

0

comments

![]()

Labels: intention, memory, personal identity, Self to Self, Velleman

This week the workshop will discuss David Velleman's essay "Self to Self", which is collected in his book Self to Self.

We will meet on Wednesday, November 1st in Cobb 103.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

10/30/2006

0

comments

![]()

Tonight the workshop met to discuss readings for the upcoming year. We quickly narrowed the field to Campbell's Reference and Consciousness and Velleman's Self to Self. There were some outside agitators (Dan G. and Micah L.) who threw their support behind the Velleman. Mind Workshop regular Will S. argued for the Campbell. A couple die-hards held out unsuccessfully for the Chalmers. The arguments weren't nearly as vehement and the votes were not as close as last year. We decided to do both the Velleman and the Campbell, starting with the Velleman.

The workshop meets again in two weeks.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

10/04/2006

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Administrative, Campbell, Chalmers, Velleman

The Philosophy of Mind Workshop will meet in even weeks this quarter, beginning Wednesday, October 4th. We will meet in Cobb 103 from 6-8pm.

(Pictured above are some of the sources for past readings discussed by the workshop.)

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

9/20/2006

0

comments

![]()

Labels: fall, meeting time

Summer is nearing its end. Or at least it as most places. Here at the U of C we still have another month or so.

Back in the spring, at the final meeting of the 2005/2006 workshop year, we decided on a shortlist of books to vote on in the fall. The shortlisted works are the following:

Reference and Consciousness, by John Campbell.

Self to Self, by David Velleman.

What's Within, by Fiona Cowie.

The Conscious Mind, by David Chalmers.

I've also added some new features, including a new list of philosophy links and a list of previous workshop readings. They're over on the sidebar. Enjoy.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

8/28/2006

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books summer readings

(The image above is the result of plugging the mind workshop into the website Websites as Graphs.)

The Philosophy of Mind Workshop is now on summer vacation. Any posts here will be infrequent and short until school starts back up again in the fall.

Enjoy the summer.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

6/11/2006

0

comments

![]()

Tonight the workshop met for the last time this academic year. We discussed the last two chapters of Sense and Sensibilia and what we might read in the fall.

I will post a synopsis of our discussion of Austin shortly.

We decided on four possible books for the fall:

1. John Campbell, Reference and Consciousness

2. Fiona Cowie, What's Within: Nativism Reconsidered

3. David Chalmers, The Conscious Mind

4. David Velleman, Self to Self

-------------------------------------------------------------

Sense and Sensibilia, Chapters X and XI

David F. was on point tonight for the workshop. He got things going by asking three questions about the penultimate chapter in S&S:

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

6/01/2006

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Austin, perception, Sense and Sensibilia, sense data

On Wednesday the workshop met to discuss a short paper of Russell Rolff’s on Timothy Williamson and chapters VIII and IX in Austin’s Sense and Sensibilia. What follows is a summary of our discussion of Austin.

Jason was our lone faculty representative because David was off giving a paper in Scandinavia. He (Jason) began discussion by focusing attention on Austin’s argument against Ayer’s claim that there are “different senses” of “’perceive’ and other verbs designating modes of perception” (87). Ayer wants to argue for the claim that sense-data talk is just a “clearer and more convenient” way of talking about the objects of perception (87). How does he reach that conclusion? Austin presents Ayer’s argument as follows:

1. There are several different senses of the word “perceive”: In one sense of the word, saying that I perceive an object means that “it is necessary that what is seen should really exist, but not necessary that it should have the qualities that it appears to have”; while in another sense, “it is not possible that anything should seem to have qualities that it does not really have, but also not necessary that what is seen should really exist”.

2. Some philosophers use the word “perceive” or “see” as a kind of mongrel version of both senses of “see” just described. That is, they use “see” and “perceive” in such a way that it has the sense that what is seen must exist, and that it must have the properties that it appears to have (86). But since in delusive situations, what is “seen” either doesn’t really exist or doesn’t have the properties it appears to have, they are thereby obligated to find an object that both exists and has the relevant properties. That object is a sense-datum.

3. Next, these philosophers “find it ‘convenient’, Ayer says, ‘to extend this usage to all cases’, on the old, familiar ground that ‘delusive and veridical perceptions don’t differ in ‘quality’” (87).

4. So, in all cases of perception, “the objects of which one is directly aware are sense-data and not material things…[this] enables us only to refer to familiar facts in a clearer and more convenient way”.

Austin fastens on Ayer’s claim that there are different senses of “perceive” and “see”. Austin denies that the evidence that Ayer offers in support of this claim establishes that there are different senses for “perceive” and “see”. discusses a number of different examples given by Ayer in support of the claim that there are different senses of “perceive”. For each example, Austin tries to show that instead of finding different senses of “see” or “perceive”, there are other perfectly acceptable ways of avoiding apparent incompatibility.

For example, Ayer says “If I say that I am perceiving two pieces of paper, I need not be implying that there really are two pieces of paper there” (89). Interestingly, Austin agrees with Ayer on this point, that we can say that we are perceiving two pieces of paper without thereby implying that there really are two pieces of paper we are seeing, as in a case of double vision (90).

But Austin stops short of finding a different sense of “perceive” in this case. He says that in normal circumstances, saying that you perceive two pieces of paper entails that there are two pieces of paper, but “we may have to stretch our ordinary usage to accommodate” the “exceptional case” of double vision (90-91). He then says that to say “I am perceiving two pieces of paper” in the case of double vision is to say that faute de mieux (for lack of something better), and that “the fact that an exceptional situation may thus induce me to use words primarily appropriate for a different, normal situation is nothing like enough to establish that there are, in general, two different, normal (‘correct and familiar’) senses of the words I use” (91).

Jason was quick to point out that this line of handling the different senses of “perceive” seems at odds with the way that neo-Austinians like Charles Travis want to handle similar situations by saying that words do have different senses (truth-conditions) in different circumstances.

That is part of Austin’s response to Ayer’s claim that there is a sense of “perceive” that does not require that the object that is said to be perceived actually exist. He then takes up Ayer’s claim that there is a sense of “perceive” that does not entail that the object seen has the characteristics (properties) it appears to have.

Austin then discusses Ayer’s case of a man, gazing into the starry heavens, says both (a) “I see a distant star which has an extension greater than that of the earth”; and (b) “I see a silvery speck no bigger than a sixpence”. Since nothing can both be a silvery speck no bigger than a sixpence and have an extension greater than that of the earth, Ayer says that “one is tempted to conclude that one at least of these assertions is false” (92). Of course, Ayer (like Austin) thinks that both assertions can be true, and he tries to make room for the truth of both statements by saying that there are two different senses of “see” at work in this case, one which does not require that the thing seen have all the properties which it appears to have (this is the sense present in (a)), and one according to which “it is not possible that anything should seem to have qualities that it does not really have, but also not necessary that what is seen should really exist” (94). This second sense is supposed to be the sense operative in (b), above—the case of the silvery speck.

What does Austin say about this case? Though he finds the first sense “a bit obscure”, he thinks it is “probably all right”. He focuses his attention on the second sense. He first observes that saying that you see a silvery speck “of course ‘implies’ that the speck exists” (94). And then he says that there is no legitimate distinction that can be drawn between merely seeming to be no bigger than a sixpence and being no bigger than a sixpence (95-96). I take the point of Austin’s observation to be that the best way to understand “I see a silvery speck no bigger than a sixpence” is as “I see a silvery speck that appears no bigger than a sixpence” (if I remember correctly, Will suggested something like this in the workshop). So it looks like Austin is saying that rather than find multiple senses for “see”, we find different senses of “is” here. Austin takes this to show that there is no second sense of “sees” as suggested by Ayer.

Jason then asked about the intriguing footnote on p. 95. Austin says:

“What about seeing ghosts? Well, if I say that cousin Josephine once saw a ghost, even if I go on to say I don’t ‘believe in’ ghosts, whatever that means, I can’t say that ghosts don’t exist in any sense at all. For there was, in some sense, this ghost that Josephine saw. If I do want to insist that ghosts don’t exist in any sense at all, I can’t afford to admit that people ever see them—I shall have to say that they think they do, that they seem to see them, or what not”.

Jason thought this was odd. If you say that cousin Josephine once saw a ghost, why not say that you’re saying something that is obviously false and implicating that she believes that she saw one? That way we needn’t have to say, even in some sense, that there was a ghost that Josephine saw. That sounded reasonable enough—those who believe in ghosts, even in some sense, don’t need any aid and comfort from ordinary language philosophy.

The workshop will meet again on May 31 to discuss the rest of Sense and Sensibilia and a paper by Rachel Goodman.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

5/24/2006

0

comments

![]()

Professor Thomas Baldwin (University of York) will give a talk, "Perception, Reference, and Causation" to the Mind Workshop tomorrow night.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

5/09/2006

0

comments

![]()

Last night the workshop met to discuss chapters V-VII in J.L. Austin's Sense and Sensibilia, after Jay and I talked about McTaggart's argument for the unreality of time.

David F. was at bat tonight. He started discussion by pointing to Austin's discussion, in chapter VII, of the word "real". Austin convincingly shows that for sentences containing the word "real", "you can't tell what I mean just from the words I use; it makes a difference, for instance, whether [certain other contextual conditions hold]" (65). Austin makes a point of contrasting this feature of sentences containing the word "real" (a feature it shares with certain other words, like "good") with sentences like "This is pink". Austin says that "whereas we can just say of something 'This is pink', we can't just say of something 'This is real'" (69).

But is the contrast that Austin draws correct? That is, is it right to say that we can just say of something that it is pink? If you say "The book is pink", is there only one way that the world has to be in order for the sentence to be true? It doesn't seem so. The book might have a pink dust jacket, pink pages, a pink title on the spine, and so on. And merely supplying a substantive for "real" to attach to, e.g., "That is a real duck", doesn't yet pick out only one way that the world could be make the sentence true. For example (adopting an example from Travis), an utterance of "That's a real duck", said while demonstrating a decoy duck, would be false if the speaker was trying to distinguish decoys from living ducks; but an utterance of the same sentence, said while demonstrating the same decoy, might be true if the speaker was trying to distinguish decoy ducks from decoy coots (duck look-alikes).

David pointed to Austin's discussion of the statement "That isn't the real colour of her hair" (65). David said that you could delete each occurrence of "real" in the passage without any change in the significance of the passage. For example, consider the passage with every occurrence of "real" omitted:

"But suppose (a) that I remark to you of a third party, 'That isn't the colour of her hair.' Do I mean by this that, if you were to observe her in conditions of standard illumination, you would find that her hair did not look that colour? Plainly not--the conditions of illumination may be standard already. I mean of course, that her hair has been dyed, and normal illumination just doesn't come into it at all. Or suppose that you are looking at a ball of wool in a shop, and I say, 'That's not its colour'. Here I may mean that it won't look that colour in ordinary daylight; but I may mean that wool isn't that colour before its dyed."

There was some dispute about whether David's bold claim was correct, but it does seem correct to think that "real" does not contrast as clearly with other terms like "pink" or "colour of her hair" that Austin wants to contrast it with. There was some discussion of how best to characterize the difference between sentences containing "real" and sentences not containing it.

Next, we found fault with Austin's treatment of the "cricket" example on p. 64. Austin compares the word "real" with the word "cricket", and says that "words of this sort have been responsible for a great deal of perplexity". He then says,

"Consider the expressions 'cricket ball', 'cricket bat', 'cricket pavilion', 'cricket weather'. If someone did not know about cricket and were obsessed with the use of such 'normal' words as 'yellow', he might gaze at the ball, the bat, the building, the weather, trying to detect the 'common quality' which (he assumes) is attributed to these things by the prefix 'cricket'. But no such quality meets his eye; and so perhaps he concludes that 'cricket' must designate a non-natural quality, a quality not to be detected in any ordinary way but by intuition."

But, it was pointed out (by Jason or David or Jay), if someone didn't know about any topic, including "yellow", then the person might gaze at yellow teeth, a yellow book, a yellow lightbulb, etc. and find no 'common quality' which is attributed to these things by the preflix 'yellow'. Of course, not knowing anything about cricket or yellow, a person might find the common quality shared by yellow things or all things cricket mysterious! Whereas, someone who knows about cricket or yellow would be able, presumably, to identify the shared quality involved--something having to do with the game of cricket, on one hand, and with yellowness, on the other.

As the workshop wound down, Jason and David were interested in finding out what our assessment of the book was. They both related stories from their grad student days where prominent philosophers (McDowell, Stroud) expressed their respect for the book. Jason and David said that they thought the book may be of more historical than lasting philosophical significance. There was some debate about that--Ben was the most eloquent defender of the book's lasting significance. He said that Austin demonstrates an admirably assiduous approach to philosophy that, instead of racing ahead and generating "results", stops and tries to work out what problems, if any, are actually being solved by the philosopher, and whether they are worth solving.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

5/04/2006

2

comments

![]()

Last night, Jay and I presented some material on McTaggart's argument for the unreality of time. What follows is part of what we talked about.

McTaggart’s Argument

1. Time essentially involves change.

2. Change can only be explained in terms of A-series expressions.

3. A-series expressions involve contradiction and so cannot describe reality.

4. So time is unreal.

Lowe wants to resist (4). He does so by denying (3). But his denial of (3) requires altering McTaggart’s account of (2) to explain how change can only be explained in terms of A-series expressions. Lowe’s argument can therefore be broken down into two parts. Part I: Denying that A-series expressions involve contradiction. Part II: explaining how change essentially involves A-series expressions.

PART I: Denying that A-series expressions involve contradiction

1. McTaggart’s argument for (3) involves the following claims:

a. The predicates “is past”, “is present” and “is future” all apply to all events

b. These predicates are inconsistent

2. An initial response: “past”, “present”, and “future” do not apply to all events at the same time.

3. Two versions of this response:

a. A-series version, second-level tenses: Event e is present (in the present), is future (in the past), and is past (in the future).

b. B-series version, indexing tenses to dates: Event e is present in 2006, is future in 1978, and is past in 2034.

4. Traditional problems with each response:

a. Traditional problem with A-series version (given by Dummett): The contradiction is not eliminated. Event e is not only present (in the present), it is also past (in the present) and future (in the present); or it is not only future (in the past), but past (in the past) and present (in the past). Each group of higher level A-series expressions is contradictory.

b. Traditional problem with B-series version: The contradiction is eliminated, but the A-series is reduced to the B-series. “Event e is present in 2006” is equivalent to “Event e is simultaneous with 2006”; “Event e is future in 1978” is equivalent to “Event e is after 1978”; and “Event e is past in 2034” is equivalent to “Event e is before 2034”.

5. Lowe’s new problems with each response:

a. A-series version: Higher-order tenses are incoherent (66). Tenses function like indexicals. Indexicals get their content from the context of utterance. The context of utterance cannot be shifted. David Kaplan says that attempts to shift the context in which indexicals get assigned their contents generate “monsters”. It doesn’t make sense to say that in the future, it is the present, just as it doesn’t make sense to say it is here over there or To you, I am you.

b. B-series version (Sorabji): Indexing A-series expressions to times is also incoherent, for the reasons just given. Saying “Event e is future in 1978” attempts to shift the context of utterance for “is future” back to 1978. But we can’t do that.

Jason worried that Lowe's intuitions about the incoherence of utterances like "In the future, 2006 will be past" were wrong. It seems perfectly possible to say something like, "Back in 1984, my college years were still in the future" without lapsing into incoherence.

PART II: Explaining how change essentially involves A-series expressions

7. McTaggart explained change in terms of future event e becoming present and receding into the past (68). But Lowe can’t use this explanation of change, because the idea of an event going from being present to being past is what generated the contradiction in the A-series. So how does Lowe explain change?

8. Lowe’s explanation of change in terms of sequences:

a. Lowe thinks he can show how change is essential to time in a way that it isn’t for space: “In all the possible space-time routes a person may take, the order of temporal positions will be the same, while the order of spatial positions may vary” (69).

i. A Worry: How does this show that change is essential to time, and not to space? It seems if anything it shows that change is essential to space, since the temporal sequences of the routes a person may take are always the same.

9. But granting that Lowe has shown that change is essential to time, why does he think that change essentially involves A-series expressions?

a. Lowe has explained how change is essential for time in terms of possible variations in space-time sequences: an active person may take sequence <(s1, t1), (s2, t2), (s3, t3)>, or a couch-potato may take sequence <(s1, t1), (s1, t2), (s1, t3)>, but both the active person and the couch potato will have sequences that must have the form <(-, t1), (-, t2), (-, t3)>. What about these sequences involves anything about the A-series? We could, for example, fill in the time variables with B-series dates: <(-, May 2, 2006), (-, May 3, 2006), (-, May 4, 2006)> (69). If the sequences that explain how time essentially involves change don’t essentially involve the A-series, then Lowe has rejected premise (2) in McTaggart’s argument, which he doesn’t want to do (63).

b. Lowe’s response: Routes are sequences of “spatio-temporal perspectives” (69). What does this mean? It means that routes can’t rely on anything like non-perspectival, non-tensed, non-indexical ways of specifying times (and locations?). Perspectival sequences would look like this: <(there, yesterday), (here, today), (there, tomorrow)>; <(here, yesterday), (here, today), (here, tomorrow)>.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

5/04/2006

0

comments

![]()

This week, the workshop will meet in Cobb 104 on Wednesday from 6-8pm to discuss pp. 44-77 of J.L. Austin's Sense and Sensibilia, as well as the following (short) papers on McTaggart's argument for the unreality of time:

E.J. Lowe, "The Indexical Fallacy in McTaggart's Proof of the Unreality of Time"

Michael Dummett, "A Defense of McTaggart's Argument for the Unreality of Time"

Peter Geach, selection from "Time" in Truth, Love, and Immortality

I'll send out the Geach as soon as I get it scanned.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

5/01/2006

0

comments

![]()

The philosophy of mind workshop blog is roughly one year old. In that time, we have become a destination for those doing google searches on the following topics (these are just a few examples from the past couple of days):

"functionalism and anomalous monism"

Brandom+beliefs+knowledge

Donnellan phenomenon

philosophy naming and necessity what is in a name

jl austin other minds

q-memory parfit

kripke on donnellan's counterexamples of russell

Speaker's reference and semantic reference

Quine's "Word and Object"

Sellars game of giving and asking for reasons

Dennett philosopher criticizes Descartes

We also occasionally get visitors who want to know things about:

Insurance Poets

One of the damn things is enough

globula

pickledork

Zed Adams

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

4/26/2006

1 comments

![]()

Tonight the workshop met for a double shot of J.L. Austin.

First Ben McMyler offered his revisionary reading of Austin's "Other Minds".

Then we discussed chapters I-IV of Sense and Sensibilia.

Jason gave a characteristically lucid and provocative account of Austin's way of responding to the argument from illusion.

The Argument From Illusion (As reconstructed by Jason)

(1) An example of a deceptive or illusory experience of an F is given.

(2) In such a case you see or experience something F.

(3) In such a case you're not seeing/experienceing a material F.

(4) Therefore, in such a case, you must be experiencing an F-ish sense datum (you must be experiencing something that is F or F-like).

------------------------------------------------------------

This first stage of the argument from illusion does not yet purport to establish the more ambitious claim that a subject is always experiencing a sense-datum, even in non-deceptive/illusory cases. To get to that conclusion, we need to add the following:

(5) A deceptive experience of an F can be indistinguishable from a veridical experience of an F.

(6) The deceptive and the veridical experiences, when indistinguishable, must have the same content (be of the same thing).

(7) Therefore, what we see/experience in both cases is a sense datum.

(8) Therefore, you only ever see an F indirectly.

Obviously, there are various problems with the argument as outlined above. Jason eventually wondered why Austin picks on the argument in the particular way(s) that he does in S&S. But first Jason said that he thought that the primary motiviation for invoking sense data is anti-skeptical, and that the argument from illusion is meant only as a secondary move to "buttress" the introduction of sense data.

How does Austin criticize the argument from illusion? Jason suggested two possible ways of reading Austin's criticisms. Either Austin simply tries to show that one or more of the premises of the argument is false, or, more ambitiously, he tries to show that all attempts to formulate the argument from illusion are confused.

I said that in his discussions of the bent stick, the mirror, and the mirage, Austin seems to criticize different parts of the argument. For example, Austin agrees that when one sees a straight stick placed in water, it makes sense to say that it looks bent. But, in the following passage, Austin seems to take issue with both (2) (3) in the argument given above:

"...we are told, in this case you are seeing something; and what is this something 'if it is not part of any material thing'? But this question is, really, completely mad. The straight part of the stick, the bit not under water, is presumably part of a material thing; don't we see that? And what about the bit under water?--we can see that too. We can see, come to that, the water itself. In fact what we see is a stick partly immersed in water..." (p.30).

In the mirror case, Austin clearly rejects (3), that when it "appears [that my body] is some distance behind the glass" (p.31), "I am not seeing a material thing". He also says that I see the mirror, and I see my body in the mirror, which suggests (to me, at least), that Austin is also rejecting premise (2), that when it appears that F (that my body is behind the glass), I must experience something F-ish (something behind-the-glass-ish). No--what I'm experiencing/seeing is the mirror and my body "in" the mirror.

Austin seems to grant (1-3) in the case of the mirage, but denies that it follows that the person experiencing the mirage is "experiencing sense-data" (p.32).

After I described the different ways Austin approaches the examples, Jason asked whether the key premise in the argument from illusion is (2). It seems possibly the least plausible premise in the argument. Focusing on it might have made shorter work of the argument from illusion. Why spend time picking apart the language of those arguing for sense-data rather than going straight to the heart of the argument?

Zack then said that he thought he could modify the argument to make premise (2) more plausible. If (2) is changed to read:

(2') In such a case you see or experience something

(2') might be something that Austin accepts. In each case Austin discusses, Austin clearly thinks that we are seeing something: a stick submerged in water; our reflection in a mirror; and a mirage. So it might turn out that rejecting premise (2) isn't enough to bring down the argument from illusion.

Jason then said that he thinks Austin's way of criticizing his opponents is excessively uncharitable. Instead of trying to give a rational reconstruction of Price or Ayer's arguments, Austin is content merely to point out their mistakes.

Jay, sympathizing with Jason, contrasted Austin's philosophical method with Wittgenstein's. While Wittgenstein treats the confusions of the philosopher as confusions that we are all prone to, Austin treats them as careless mistakes.

(This difference was disputed, to some extent, by some members of the workshop, including I think Ben and maybe David F.)

We meet again in two weeks to discuss more of Sense and Sensibilia.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

4/19/2006

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Austin, perception

This week, the workshop will meet on Wednesday, at 6pm in COBB 104 (note room change) to discuss a paper by Ben McMyler and the first 43 pages of Sense and Sensibilia.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

4/17/2006

0

comments

![]()

Jason, Zed, Erica, (prospective student), Josef, Jesse, (psychology grad student), Melody, Roscoe.

Not pictured: Gary, Will, and me.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

4/13/2006

0

comments

![]()

The first meeting of the Philosophy of Mind workshop will be Wednesday, April 5th.

We will meet in Cobb 119 from 6pm-8pm.

Zed Adams (pictured above) will be presenting his paper, "A Defence of Colour Primitivism". (He insisted on "color" being spelled with a "u", and "defense" with a "c".) Zed has asked us to read the following two things in preparation:

(1) Byrne and Hilbert, "Color Primitivism"

(2) Austin, "Sense and Sensibilia", pp. 65-68 (beginning with "Let us begin, then with a preliminary ..." and ending with "not a real duck". (The page numbers may vary from edition to edition. Zed has the 1976 edition.)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

For the second half of the workshop, we will discuss pp. 1-43 in Austin's Sense and Sensibilia.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

3/29/2006

0

comments

![]()

Jesse Prinz, Associate Professor at UNC Chapel Hill and U of C alum, will give a paper to the workshop on April 6:

"Hume's Brain: How Cognitive Science Supports British Moral Psychology"

The event will be co-sponsored by the Contemporary Workshop and by the Nicholson Center for British Studies.

Here is a link to Jesse's homepage.

The talk will be in Cobb 107 from 6pm to 8pm.

See you there.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

3/13/2006

0

comments

![]()

Tonight we talked about my paper on contextualism. We concentrated on MacFarlane's non-indexical contextualism. You can get MacFarlane's paper on his website here.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

3/08/2006

1 comments

![]()

The reading for this Wednesday's meeting of the workshop is ch. 8, pp. 495-547.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

2/20/2006

0

comments

![]()

Last Wednesday the workshop met to discuss parts I and II of chapter 4 of Brandom's Making It Explicit.

Part I

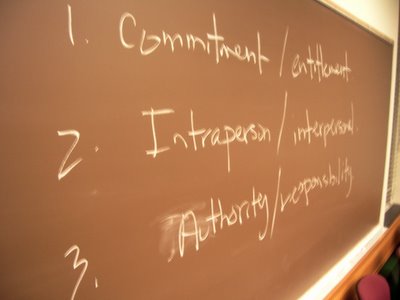

Jason kicked things off again with a short intro to Brandom's account of observational knowledge and knowledge in general. Brandom wants to give an account of both in terms of the varieties of his deontic statuses of commitment and entitlement. Ascribing knowledge is taken as the basic explanandum.

Brandom takes knowledge to be an amalgam of belief, truth and justification, and assigns particular deontic statuses to correspond with each feature of the traditional analysis of knowledge. (He says that if the Gettier counter-examples show that knowledge cannot be analyzed as justified true belief, then what he is giving an account of is knowledge*, which just is justified true belief.) Here is how the three elements are translated into Brandomese:

1. Belief

When I ascribe knowledge to someone, e.g., "Aidan knows he is undefeated at squash", I attribute certain commitments to Aidan. For Brandom, that means Aidan is prepared to make certain assertions and draw certain inferences.

2. Justification

In ascribing knowledge to Aidan, I not only attribute a commitment to him, I attribute entitlement as well. This corresponds to justification in the traditional picture of knowledge.

3. Truth

Finally, I myself undetake a commitment to make those assertions and draw those inferences that I attributed to Aidan in (1). This is supposed to correspond to the truth element in the traditional model.

Jason raised a couple questions about Brandom's way of handling knowledge. First, for Brandom, the three elements out of which knowledge is composed are separable. One could attribute commitment and entitlement to Aidan without oneself undertaking a corresponding commitment. Jason said that this meant that Brandom was committed to the possibility of reducing knowledge into justification, belief and truth components. (Though, to be fair, Brandom does make the remark about his giving an analysis only of knowledge* mentioned above. But one might object to that move by just saying Brandom has left knowledge untouched.)

Second, Jason worried that Brandom's account of knowledge in terms of ascriptions of knowledge made knowledge far too external to the knower. It seems possible, on the face of it, to be a knower without there being any other subjects around. Brandom clearly thinks that knowledge is a status that one has only in virtue of being part of a certain kind of social practice. If there aren't any attributers around, then how can I count as believing truly or being justified? David and Jason both raised the possibility that Brandom might respond by saying that we could understand such a situation by saying that it would be appropriate to attribute entitlement and undertake corresponding commitment, and what would be appropriate would constitute my status. But that option seems unavailable to Brandom, since the way "appropriateness" would have to be understood here would require saying something about how what I believe is true, and he has himself said that he isn't entitled himself to that all-important norm yet.

(But, I wonder, thinking about the objection now as I write it down, whether there isn't a simpler response for Brandom to make to Jason's objection. He might simply say, in the situation where there aren't any other attributers around, that the knower himself ascribes knowledge to himself. The only odd feature of this suggestion is that such a subject would attribute a commitment to himself and then undertake the same commitment, which seems a bit superfluous. But, presumably, the same situation would arise in a social situation where I want to ascribe knowledge to someone and I already am committed to what I attribute to him.)

Jason then turned to Brandom's account of observational knowledge.

There is a picture of observational knowledge according to which when I experience that p, I don't thereby immediately come to believe that p. The content of my experience is something like an appearance that p. An appearance that p can serve as a reason to form the belief that p, and when I have good enough reasons in support of the belief that p, I count as knowing that p.

That picture of observational knowledge is not Brandom's. For Brandom, experience plays no role in the constitution of observational knowledge. Observation consists simply in forming a belief in the right way. Brandom inherits this picture of observational knowledge from Sellars, though he "socializes" Sellars's picture in the following way. Sellars holds that observational knowledge consists in a reliable belief-forming process yielding a belief that a knower can then explain in the right way by giving reasons in support of his belief if challenged. Brandom amends Sellars's view by saying that it needn't be the knower himself who is in a position to give reasons in favor of the belief if challenged. It can be someone else speaking on the knower's behalf. A knower need not be aware of his own reliability at all. (Thus the strange case of Monique and the hornbeams. Even though she disavows knowledge that the tree she sees is a hornbeam, she can count as a knower if someone is able to give reasons on her behalf.)

Jason's third and final question concerned the distinction between (1) what you observe to be so and (2) what you experience to be so. He said that it was questionable whether the physicist observing the bubble chamber actually experienced the mu-meson, or merely came to know it via observing it. Jason felt that there was a big difference between experiencing that p then inferring from what one experiences to q, where q can count as observational knowledge. And Jason said that he thought Brandom was in trouble because he wouldn't be able to draw this intuitive distinction between experience and observation. There was a great deal of debate about this claim over the course of the workshop.

We wondered what a bubble chamber looked like. I found a picture of one:

And here is a picture (how it was made, I don't know) of some collisions in a bubble chamber:

At this point, we couldn't contain ourselves any more and discussion began.

Part II

I asked if Jason's last objection was a version of the familiar "blindsight" objection to Brandom's account of observational knowledge. That objection, roughly, is that Brandom's account of observation can't distinguish between, e.g., normal seeing and blindsight (if blindsight were a reliable belief-forming mechanism). Jason seemed to think that yes, his objection was a version of this worry. I then formed a version of the blindsight objection based on the fact that for Brandom, what distinguishes the beliefs that form part of the status of observational knowledge from other beliefs is that they are non-inferentially acquired. But beliefs might be non-inferentially acquired without being observational. For example, you might be wired up so that someone implants beliefs in you about some distant location. Would such a non-inferentially acquired belief count as observational? It seems intuitive that it would not. But it seems that Brandom would not have the resources to deny that it was. Jason seemed sympathetic to this kind of worry.

Aidan defended Brandom on this point, claiming that he never understood why people thought these kinds of blindsight objections were effective against Brandom or Davidson. He said that given a suitably coherent enough set of beliefs suitably related to one another, observational (perceptual) beliefs might perfectly well be distinguished from other kinds of belief.

Jason replied by saying that a series of beliefs that were arrived at by way of some non-observational process, like some implanted device, might be coherent and connected and yet they still wouldn't count as observational.

David then defended Aidan. He said (citing Dennett, I think), that "taken far enough", the requirements of suitable connection and coherence would amount to what we would recognize as observation, and that experience would at that point just be a superfluous add-on.

Jason seemed unconvinced, but we moved on (though Jason and Aidan sparred over this issue again at the end of the workshop).

Part III

Since Jason wasn't feeling well, David helped out with a short presentation.

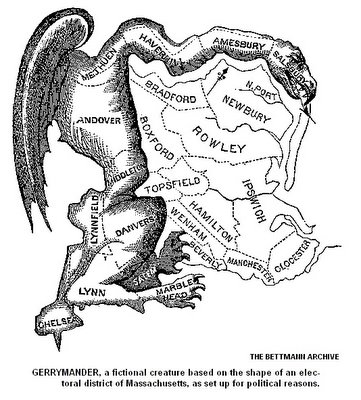

David began by asking if anyone could explain Brandom's talk of "gerrymandering" that appeared in Brandom's rejection of regularism in chapter 1. I thought I had some idea of why he was using that term, having to do with the drawing of arbitrary boundaries, but I had to admit that extending it to the case of failed solutions to the rule-following argument always seemed a bit of a stretch. But David then answered his own question by giving a superb explanation of the metaphor of gerrymandering as it appears in chapter 4 and in chapter 1.

The gerrymandering metaphor, David explained, has its natural home in Brandom's discussion of reliabilism. Brandom thinks that there is a gerrymandering problem that afflicts reliabilist accounts of knowledge that is analogous to the gerrymandering problem for the regularist response to the rule-following problem. The problem is that whether or not one counts as reliable depends on what one considers relevant possibilities. So, in Goldman's example, the subject correctly identifies a barn. But if the barn is the only real barn in a county full of fake barn facades, our intuitions incline towards rejecting the subject's claim to be a reliable reporter of barns. But if we widen our view a bit, and take in the whole country, where barn facade county is an anomaly, then it seems that the subject does count as a reliable reporter of barns, and so does count as knowing that he's viewing a barn. But then maybe in the whole universe there are many more worlds that are full of fake barns and in such worlds the subject wouldn't count as a reliable reporter of barns. So it appears that depending on how we demarcate the relevant domain within which the subject has to identify barns, we get different assessments of his reliability. Brandom's gerrymandering charge against the reliabilist amounts to the claim that there is no way for the reliabilist to justify treating one way of drawing the boundary as more appropriate than any other. So it looks like we have no reason to say that the subject in Barn Facade County is reliable as opposed to unreliable.

In the case of Goldman's barn facade county thought experiment, the effect of drawing arbitrary boundaries (in this case, geographical boundaries) becomes apparent, and the metaphor of gerrymandering makes good sense.

How does the metaphor apply to the rule-following argument?

The regularist, dispositionalist reponse to the rule-following argument has a boundary problem as well. Say we try to give a dispositionalist account of a concept like "horse". We say that the concept consists just in my disposition to call certain things horses. But then we have a problem because not all the things I'm disposed to call a horse are actually horses. So how do we rule those cases out? Even if we say that a horse is what I am disposed to call a horse in favorable conditions, there will still be situations in which I call something that isn't a horse a horse. The upshot is that to actually draw the appopriate boundary, it looks like I'm going to have to cheat and bring in the concept horse, which is what I was trying to give a reductive account of.

In both the regularist response to the rule-following argument and in the reliabilist account of knowledge, we want a non-arbitrary way of drawing the relevant boundary that doesn't simply rely on our intuitive grasp of the concept we're trying to get a handle on.

I liked David's explanation of the gerrymandering metaphor, but I had a question about Brandom's "solution" to the gerrymandering problem for the reliabilist. Roughly, his solution to the problem, his way of fixing the relevant boundary, is to rely on the attitudes of subjects--basically, if I have understood him correctly, that we decide what the relevant boundary is:

"What in practice privileges some of the reference classes with respect to which reliability may be assessed over other such reference classes is the attitudes of those who attribute the commitment whose entitlement is in question" (p. 212).

I worried that this wasn't a real solution to the boundary problem, since there is nothing to suggest that the attributers will agree on where the boundary should be drawn. Should the subject's reliability then be attributer-dependent? Maybe, but then whether a subject counts as reliable depends completely on the vagaries of his attributers. It would sure help here to be able to simply say that the boundary should be drawn according to the attitudes of those attributers who correctly assess where the boundary should be, but of course Brandom can't take that route.

The workshop wound down with a debate between Jason and Aidan on the role of experience in observational knowledge, which I'm afraid I can't accurately reproduce here. I'd be happy to add anything to this report that they suggest.

We agreed that instead of reading Brandom's account of action, we would jump ahead to chapter 8 next time, in order to silence once and for all the constant response to any tough questions:

"Wait until chapter 8".

See everyone in two weeks.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

2/13/2006

1 comments

![]()

The workshop will meet this Wednesday, at 6:30pm in Cobb 104 to discuss pp. 199-229 in chapter 4 of Brandom's Making It Explicit.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

2/06/2006

0

comments

![]()

Last night the workshop met to discuss the last two sections of chapter 3 in Making It Explicit.

Thanks again to Russell for taking me to get the provisions for the workshop.

Part I (Pictured: three dimensions of assertional significance)

(Pictured: three dimensions of assertional significance)

David F. gave the introduction tonight. His raised a number of different questions for consideration.

1. He began by drawing our attention to the central role that Brandom thinks assertion plays in the "game of giving and asking for reasons". Assertions, unlike actions and perceptions (reliable acquisitions of assertional commitments (RAAC)), can both stand in need of and be offered as reasons. Actions cannot (according to Brandom) serve as reasons (p.171), and perceptions (or RAACs) cannot stand in need of reasons. Later in the workshop, Jason asked whether this gloss on what assertion is amounted to a definition of assertion. It seems far too sketchy to count as a definition, since one might reasonably think (for example) that actions can be offered as reasons for assertions or further actions, as well as standing in need of reasons. (A secret handshake, for example, might be a reason for letting you-know-who into you-know-what.) To say that actions don't amount to assertional reasons is obviously to beg the question.

2. David said that there are three ways for a subject to be entitled to an assertion: (i) he can give a reason for p; (ii) he can defer to a person who asserted p; (iii) he can be entitled to p on the basis of perception. (This picture of entitlement was also called into question later in the workshop, because it looks like Brandom is committed to the idea that one can be entitled to assert p if no one challenges the assertion. More on that later.) David pointed out that many philosophers think that if the only ways that subjects were entitled to assert p were (i) and (ii) (which correspond to inference and testimony, respectively), there would be a vicious regress of entitlement. Sellars, for example, thinks we need perception to entitle (justify) us to assert p in order to halt the regress. But, interestingly, it looks like Brandom isn't too concerned with this kind of traditional worry about a regress of entitlement. On p. 177 Brandom says that "the worry about a regress of entitlements is recognizably foundationalist", and that he responds to the worry by introducing the idea that "if many claims are treated as innocent until proven guilty...the global threat of regress dissolves". Jason raised a worry about this purported dissolution of the regress by asking how a simple fact about the structure of the game of giving and asking for reasons was supposed to alleviate any worries about justification. (Though, to be fair to Brandom, the fact about the game of giving and asking for reasons is supposed to be constitutive of entitlement. But, to be fair to Jason, this just raises the question we kept asking last week: how are norms (like genuine entitlement) supposed to arise out of mere practices? We still haven't got an account of that yet, and without one, Jason's question is a serious challenge.)

3. David asked whether Brandom's view of interpersonal, intracontent scorekeeping consequences didn't involve a blurring of the difference between how we entitle addressees of an assertion to themselves assert p and how we entitle (if we do at all) mere overhearers of what we assert (see the last full paragraph on p. 186). Ben, our resident expert on all things testimonial, pretty much agreed (with some reminders about how there are more and less inclusive notions of address).

4. David next gave a quick rundown of the deontic scorekeeping project. Someone asked how many scoreboards there would have to be for such a project to work. David said that each participant would have a scoreboard, on which he would keep tabs of the scores of everyone else in the practice (presumably including a row or column, or whatever, for himself). "The force of an utterance, the significance of a speech act, is to be understood in terms of the difference it makes to what commitments and entitlements are attributed and undertaken by various interlocutors" (p. 188). David asked whether Brandom should have said ought where are is in the quote just given. Shouldn't it be the case that what significance and force an utterance of mine has depends on what effects my utterance should have, and not on those effects it happens to have? It looked like this was another place where what should be normative statuses of various kinds are being constituted by brute regularist patterns of activity.

5. After Brandom explains David Lewis's "Scorekeeping in a Language Game", he goes on to say how his appropriation of the idea of scorekeeping differs from Lewis's. Brandom says: "...the notion of linguistic scorekeeping is intended to play a more fundamental explanatory role here than Lewis has in mind for it. For he is happy to think of conversational scores as kept track of in 'mental scoreboards', consisting of attitudes he calls 'mental representations' of the score (representations, presumably, whose content is that some component of the score is currently such and such). Clearly he does not envisage a project such as the present one, in which both the nature of mental states such as belief and their representational contents are themselves to be understood in terms of their role in scorekeeping practices, rather than the other way around". Now thinking about this comment caused some consternation in the workshop, because it isn't at all clear how we are to understand how we keep score on one another without assuming some role for content. Is it supposed to be obvious what it means to "keep track" of one another's scores, attributing entitlements and commitments, without using anything like a (content-involving) that-clause?

Part II

The floor was now open for general discussion (some of which I have already penciled in, above).

1. I added to David's list of concerns by raising a worry about holism. The significance of a speech act is determined by the difference it makes to the commitments and entitlements attributed and undertaken by participants in the practice (p. 188). So, it seems, the significance of an assertion I make depends on the vagaries of those around me--how they respond, what kind of entitlement they attribute to me, and so on. How, then, can two subjects make an assertion that has the same significance? It seems overwhelmingly likely that the overall difference your assertion of p makes to the sum total of commitments and entitlements attributed and undertaken by the participants in the practice will be different than the overall difference my assertion of p makes. And there will be similar problems about how I can count as making the same assertion at two different times. David responded by saying that the holist shouldn't accept the idea that any difference of commitment or entitlement anywhere in the whole makes for a difference of significance. The holist should claim that while significance depends on, or is a function of, the whole range of commitments and entitlements undertaken and attributed, appropriately adjusted differences can correspond to the same overall significance. For example, you and I may have received different scores on every quiz taken over the course of the semester, but still end up with the same grade. So while our overall grades depend on how we do on each quiz, that doesn't mean that lower-level differences amount to a difference in significance. Jason asked whether the situation would be any different with numerical grades (the answer, I think, was: not really).

2. Ben then asked how we should understand Brandom's claim that "...issuing an asssertional performance can warrant further commitments, whether by the asserter or by the audience, only if that warranting commitment itself is one the asserter is entitled to" (p.171). Ben thought that it was odd to talk about warranting or authorizing my commitment to q by my assertion that p. He cited Brandom's earlier "Asserting" paper, saying that Brandom thinks of asserting p as just the issuing of an inference license. It struck Ben (and others) as incorrect to say that by asserting p, you thereby license or authorize yourself to be committed to q (so long as you're entitled to p). I think (though I could be wrong) that there were two different reasons offered to explain this feeling of incorrectness: (i) talk of "licensing" or "authorizing" oneself to believe q on the basis of one's asserting p looks like one is licensing one's transition from p to q on the basis of giving oneself testimony, which looks like a distortion of the epistemic relations among one's commitments and entitlements (we don't have to take our own word for p in order to be authorized to assert q); (ii) more generally, it looks awkward to say that it is the social attitudes of acknowledging commitments and attributing entitlements that constitute epistemic entitlement, for reasons discussed above (in short: how do you precipitate the norms out of the social attitudes?).

Jason offered an analogy to elucidate Brandom's picture of asserting p (so long as one is entitled to do so) as authorizing one to assert q: imagine you are volunteering to go on a dangerous quest (you assert p). Volunteering entitles you to sit at the head of the table (you're authorized to assert q). The appropriate question at this point was: to what extent is it appropriate to understand asserting on this "quest-dinner table" model? (The answer mooted was "not very".)

(At this point I should register the fact that I didn't completely follow the discussion of assertion and authorization--the account given in the last two paragraphs is the best reconstruction I could manage.)

Part III

The workshop wound down with some worries about the overall project in Making It Explicit. Jason pointed out that Brandom says in the preface that "Chapters 3 and 4 present the core theory--the model according to which a pragmatics specifying the social practices in which conceptual norms are implicit and a broadly inferential semantics are combined. It is here that sufficient conditions are put forward for the practices a community is interpreted as engaging in to count as according performances the pragmatic significance characteristic of assertions--and hence for those practices to count as conferring specifically propositional contents" (p. xxii). This claim was worrying, because, as far as we can tell, the only attempt to give "sufficient conditions" for assertions consists of Brandom's remarks about how assertions differ from perceptual reports and actions in that assertions can both serve as and demand justification by reasons. And that seems a pretty meager defense of this core part of the theory. And the worries that have been around since chapter one about what "norms implicit in practice" really amount to, if they aren't full-blooded rules, and also aren't just social regularities, have not been assuaged. As far as we can tell, Brandom hasn't really said how he avoids both of those positions he regards as unacceptable. Again, maybe we've just missed it.

Browse previous summaries of Making It Explicit here, here, here, and here.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

1/26/2006

1 comments

![]()

Zeke prodded me into creating a workshop email list. Which I did, and all of you can now sign up for. To do so, visit here.

And sign up.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

1/25/2006

0

comments

![]()

David has assigned the rest of chapter 3 of Making It Explicit for Wednesday's workshop meeting.

See you there.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

1/23/2006

0

comments

![]()

Last night the workshop met to discuss the last two sections of chapter two and the first two sections of chapter three of Brandom's Making It Explicit.

Thanks to Russell for helping me pick up the pizza and beer and Perrier.

PART I

Jason B. introduced the readings for this session. He first outlined some "reminders" of what's going on in MIE:

1. Brandom's project is to give a reductive account of semantic, representational, conceptual content. His variety of reductionism is peculiar, however, because his basic explanatory materials are normative.

2. Brandom's overarching commitment is to "strong inferentialism". Strong inferentialism is the view that content is to be explained in terms of inference and inferential articulation. An obvious assumption of strong inferentialism is that inference can be understood without relying on the notion of content.

3. Semantics is the philosophical study of content. Inferential semantics is semantics that presupposes strong inferentialism.

4. Pragmatics is the philosophical study of the relation between contentful items (speech acts, propositional attitudes, etc.) and the larger practice in which they are embedded.

5. Brandom's normative pragmatics involves taking normative (rather than merely descriptive) characterizations of practices as primitive. This is a basic difference between Brandom's project and naturalistic attempts to explain content.

6. Brandom's pragmatism involves a commitment to the claim that semantic concepts can be reductively explained in terms of pragmatic concepts (MIE, p. 143). In keeping with his commitment to normative pragmatics, Brandom wants to build up semantic content out of basic normative practices.

7. The key normative notions for pragmatics are commitment and entitlement. But these notions are not primitive. They are explained in terms of attributions: that S has a commitment to do A is, "in the first instance", a matter of having that commitment attributed to her.

We didn't contest any of the reminders Jason assembled. But we did contest how the basic normative pragmatic concepts (attributions of commitments and entitlements) were supposed to be understood.

Part II

Brandom says that attributing a commitment to A to subject S is, "in the first instance", to be disposed to sanction S if S fails to A. How should sanctioning be understood here? Brandom says that "sanctioning responses (for instance admitting versus ejecting) and the performances they discriminate (enterings of the theater) can be characterized apart from and antecedent to specification of the practice of conferring and recognizing entitlement defined by their means" (162). This is to define sanctioning "externally".

Jason then asked the following questions about the basic normative pragmatic concepts Brandom employs:

Is Brandom saying that being a sanction can be understood in non-normative terms? If so, how is a sanction supposed to be distinguished from mere bad consequences of an action? It seems that to distinguish sanctions from mere bad consequences requires norms: it seems a sanction is applied in response to a violation or deviation from some rule or standard. So we need some antecedent notion of rule or standard in order to understand any behavior is a sanction. Why does Brandom talk about "external" sanctions here at all? Doing so seems to conflict with normative pragmatics, his commitment to taking normative characterizations of practices as primitive.

The floor was then open for discussion.

Part III

Joe S. got things rolling by standing up for Brandom. He said that he didn't think that Brandom was engaged in reducing his basic pragmatic concepts to non-normative, "external" sanctioning.

Jason responded to Joe by developing the second horn of what became a dilemma for Brandom. If Brandom is not reducing attributions of entitlement and commitment to applications of external, non-normative sanctions, then how does he avoid introducing content at this early stage in his (supposedly reductive) explanatory project? Jason said that it was hard to see how you could attribute commitments or entitlements to someone without the use of a content-involving that-clause. And if attributions of commitment or entitlement can't be made without assuming a notion of content, then Brandom's reductive project, which aims to explain content in more basic terms, has stumbled as it takes its first step.

Jason asked again for an explanation of just what purpose the talk of "external" sanctions plays at this part in the book. If Brandom is really committed to normative pragmatics, why try to reduce basic normative concepts to non-normative concepts?

These questions struck me as raising issues that we had already discussed when we read chapter 1. In maybe the most well-known discussion in the whole book, Brandom explains how "applying a negative sanction might be understood in terms of corporal punishment; a prelinguistic community could express its practical grasp of a norm of conduct by beating with sticks any of its members who are perceived as transgressing that norm" (34). He uses Haugeland's complex behaviorist account in "Heidegger on Being a Person" as an illustration of a view of a "purely descriptive" (i.e., non-normative) account of sanctioning and social relations. Brandom dismisses the Haugeland proposal on the grounds that it is susceptible to the "gerrymandering" criticism levelled against regularism in Brandom's discussion of the rule-following argument. Briefly, Brandom claims that even Haugeland's complex version of regularism does not succeed in capturing correctness and incorrectness, and so "ought not to count as genuinely normative" (36).

But if Brandom objects to Haugeland's behaviorist account because it does not yield genuine norms, then why does Brandom introduce a similar account of "external" sanctions in chapter 3?

David F. said, somewhat half-heartedly, in response to my comment about chapter 1, that maybe Brandom starts with a Haugelandy view and it slowly becomes un-Haugelandy as he goes along.

Will S. agreed with Joe's original comment that it was wrong to say that Brandom was interested in a reduction of attribution to non-normative sanctioning. He pointed to Brandom's remark that "discursive practice is implicitly normative; it essentially includes assessments of moves as correct or incorrect, appropriate or inappropriate" (159). Will said that this, and other remarks suggested that Brandom doesn't conceive of his project as Haugelandy at all.

I don't think anyone would disagree with the claim that Brandom often represents his project this way, as normative all the way down.

But Jason responded to Will by saying that Brandom thinks that norms have to be instituted by something, and it appears that what he ultimately thinks they are instituted by are "external" sanctions.

David asked if it would help Brandom if he could help himself to a brute fact about whether someone should do A or not. If he was able to help himself to that idea, then obviously no reduction of attributions to non-normative sanctions would be required.

But if Brandom could help himself to a brute fact about correctness or incorrectness, it looks like he would be impaled on the second horn Jason developed: he would have to be assuming what he aims to explain--content.

Joe then asked what Jason meant by content.

Jason said that anything that was specified in a that-clause counts as content, as well as "seeing-as" or "taking-as".

David outlined the position that Brandom wants to occupy, but which we didn't yet seem to have a clear picture of: he needs a normative, but not contentful, attitude. He can't provide a merely dispositional account of his basic attitudes, and he also can't give a "fully normative" account of them, either. Jason challenged the very possibility of such a position by claiming that any attitude (and, a fortiori, any attribution of attitude) will involve content. If that's so, then Brandom's project cannot get off the ground.

During the last part of the workshop, Aidan G. tried to work out whether a complex dispositional account like Haugeland's could yield lower-level (not "fully objective") norms that would suffice to get Brandom's project off the ground, to which "fully objective" norms could later be added. It was hard to see how that kind of proposal avoided either the non-normative horn or the assuming content horn of the dilemma, but it at least held out the hope of success for Brandom's project.

With that (slightly flickering) hope in mind, we will meet again in two weeks to continue discussion of Making It Explicit.

Browse previous summaries of Making It Explicit here, here, and here.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

1/12/2006

5

comments

![]()

Dear workshoppers,

Dear workshoppers,

The reading for the next meeting of the workshop will be up to p. 166. That takes us into chapter 3.

Note that the registrar has changed our classroom to Cobb 104 and our start time to 6:30.

I believe I'm only allowed to put 20% of the total book on e-reserve (which comes to about 150 pages). So I think that it is reasonable to expect that anyone who is continuing to read the Brandom should go ahead and buy a copy of the book.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

1/05/2006

0

comments

![]()

Welcome back from winter break.

The Mind Workshop will be getting back to business next Wednesday, January 11th.

A short update before the Brandom reading is posted:

I have been updating the list of graduate philosophy conferences and will continue to do so. There are a bunch. You should apply. They are fun. Zed (an emeritus member of the workshop), for example, will travel to sunny L.A. in February to give a paper on supervenience and eat at In-N-Out.

Posted by

Nat Hansen

at

1/04/2006

0

comments

![]()