Making It Explicit, Chapter 4, Parts I and II

Last Wednesday the workshop met to discuss parts I and II of chapter 4 of Brandom's Making It Explicit.

Part I

Jason kicked things off again with a short intro to Brandom's account of observational knowledge and knowledge in general. Brandom wants to give an account of both in terms of the varieties of his deontic statuses of commitment and entitlement. Ascribing knowledge is taken as the basic explanandum.

Brandom takes knowledge to be an amalgam of belief, truth and justification, and assigns particular deontic statuses to correspond with each feature of the traditional analysis of knowledge. (He says that if the Gettier counter-examples show that knowledge cannot be analyzed as justified true belief, then what he is giving an account of is knowledge*, which just is justified true belief.) Here is how the three elements are translated into Brandomese:

1. Belief

When I ascribe knowledge to someone, e.g., "Aidan knows he is undefeated at squash", I attribute certain commitments to Aidan. For Brandom, that means Aidan is prepared to make certain assertions and draw certain inferences.

2. Justification

In ascribing knowledge to Aidan, I not only attribute a commitment to him, I attribute entitlement as well. This corresponds to justification in the traditional picture of knowledge.

3. Truth

Finally, I myself undetake a commitment to make those assertions and draw those inferences that I attributed to Aidan in (1). This is supposed to correspond to the truth element in the traditional model.

Jason raised a couple questions about Brandom's way of handling knowledge. First, for Brandom, the three elements out of which knowledge is composed are separable. One could attribute commitment and entitlement to Aidan without oneself undertaking a corresponding commitment. Jason said that this meant that Brandom was committed to the possibility of reducing knowledge into justification, belief and truth components. (Though, to be fair, Brandom does make the remark about his giving an analysis only of knowledge* mentioned above. But one might object to that move by just saying Brandom has left knowledge untouched.)

Second, Jason worried that Brandom's account of knowledge in terms of ascriptions of knowledge made knowledge far too external to the knower. It seems possible, on the face of it, to be a knower without there being any other subjects around. Brandom clearly thinks that knowledge is a status that one has only in virtue of being part of a certain kind of social practice. If there aren't any attributers around, then how can I count as believing truly or being justified? David and Jason both raised the possibility that Brandom might respond by saying that we could understand such a situation by saying that it would be appropriate to attribute entitlement and undertake corresponding commitment, and what would be appropriate would constitute my status. But that option seems unavailable to Brandom, since the way "appropriateness" would have to be understood here would require saying something about how what I believe is true, and he has himself said that he isn't entitled himself to that all-important norm yet.

(But, I wonder, thinking about the objection now as I write it down, whether there isn't a simpler response for Brandom to make to Jason's objection. He might simply say, in the situation where there aren't any other attributers around, that the knower himself ascribes knowledge to himself. The only odd feature of this suggestion is that such a subject would attribute a commitment to himself and then undertake the same commitment, which seems a bit superfluous. But, presumably, the same situation would arise in a social situation where I want to ascribe knowledge to someone and I already am committed to what I attribute to him.)

Jason then turned to Brandom's account of observational knowledge.

There is a picture of observational knowledge according to which when I experience that p, I don't thereby immediately come to believe that p. The content of my experience is something like an appearance that p. An appearance that p can serve as a reason to form the belief that p, and when I have good enough reasons in support of the belief that p, I count as knowing that p.

That picture of observational knowledge is not Brandom's. For Brandom, experience plays no role in the constitution of observational knowledge. Observation consists simply in forming a belief in the right way. Brandom inherits this picture of observational knowledge from Sellars, though he "socializes" Sellars's picture in the following way. Sellars holds that observational knowledge consists in a reliable belief-forming process yielding a belief that a knower can then explain in the right way by giving reasons in support of his belief if challenged. Brandom amends Sellars's view by saying that it needn't be the knower himself who is in a position to give reasons in favor of the belief if challenged. It can be someone else speaking on the knower's behalf. A knower need not be aware of his own reliability at all. (Thus the strange case of Monique and the hornbeams. Even though she disavows knowledge that the tree she sees is a hornbeam, she can count as a knower if someone is able to give reasons on her behalf.)

Jason's third and final question concerned the distinction between (1) what you observe to be so and (2) what you experience to be so. He said that it was questionable whether the physicist observing the bubble chamber actually experienced the mu-meson, or merely came to know it via observing it. Jason felt that there was a big difference between experiencing that p then inferring from what one experiences to q, where q can count as observational knowledge. And Jason said that he thought Brandom was in trouble because he wouldn't be able to draw this intuitive distinction between experience and observation. There was a great deal of debate about this claim over the course of the workshop.

We wondered what a bubble chamber looked like. I found a picture of one:

And here is a picture (how it was made, I don't know) of some collisions in a bubble chamber:

At this point, we couldn't contain ourselves any more and discussion began.

Part II

I asked if Jason's last objection was a version of the familiar "blindsight" objection to Brandom's account of observational knowledge. That objection, roughly, is that Brandom's account of observation can't distinguish between, e.g., normal seeing and blindsight (if blindsight were a reliable belief-forming mechanism). Jason seemed to think that yes, his objection was a version of this worry. I then formed a version of the blindsight objection based on the fact that for Brandom, what distinguishes the beliefs that form part of the status of observational knowledge from other beliefs is that they are non-inferentially acquired. But beliefs might be non-inferentially acquired without being observational. For example, you might be wired up so that someone implants beliefs in you about some distant location. Would such a non-inferentially acquired belief count as observational? It seems intuitive that it would not. But it seems that Brandom would not have the resources to deny that it was. Jason seemed sympathetic to this kind of worry.

Aidan defended Brandom on this point, claiming that he never understood why people thought these kinds of blindsight objections were effective against Brandom or Davidson. He said that given a suitably coherent enough set of beliefs suitably related to one another, observational (perceptual) beliefs might perfectly well be distinguished from other kinds of belief.

Jason replied by saying that a series of beliefs that were arrived at by way of some non-observational process, like some implanted device, might be coherent and connected and yet they still wouldn't count as observational.

David then defended Aidan. He said (citing Dennett, I think), that "taken far enough", the requirements of suitable connection and coherence would amount to what we would recognize as observation, and that experience would at that point just be a superfluous add-on.

Jason seemed unconvinced, but we moved on (though Jason and Aidan sparred over this issue again at the end of the workshop).

Part III

Since Jason wasn't feeling well, David helped out with a short presentation.

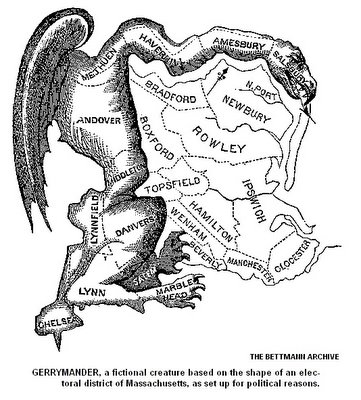

David began by asking if anyone could explain Brandom's talk of "gerrymandering" that appeared in Brandom's rejection of regularism in chapter 1. I thought I had some idea of why he was using that term, having to do with the drawing of arbitrary boundaries, but I had to admit that extending it to the case of failed solutions to the rule-following argument always seemed a bit of a stretch. But David then answered his own question by giving a superb explanation of the metaphor of gerrymandering as it appears in chapter 4 and in chapter 1.

The gerrymandering metaphor, David explained, has its natural home in Brandom's discussion of reliabilism. Brandom thinks that there is a gerrymandering problem that afflicts reliabilist accounts of knowledge that is analogous to the gerrymandering problem for the regularist response to the rule-following problem. The problem is that whether or not one counts as reliable depends on what one considers relevant possibilities. So, in Goldman's example, the subject correctly identifies a barn. But if the barn is the only real barn in a county full of fake barn facades, our intuitions incline towards rejecting the subject's claim to be a reliable reporter of barns. But if we widen our view a bit, and take in the whole country, where barn facade county is an anomaly, then it seems that the subject does count as a reliable reporter of barns, and so does count as knowing that he's viewing a barn. But then maybe in the whole universe there are many more worlds that are full of fake barns and in such worlds the subject wouldn't count as a reliable reporter of barns. So it appears that depending on how we demarcate the relevant domain within which the subject has to identify barns, we get different assessments of his reliability. Brandom's gerrymandering charge against the reliabilist amounts to the claim that there is no way for the reliabilist to justify treating one way of drawing the boundary as more appropriate than any other. So it looks like we have no reason to say that the subject in Barn Facade County is reliable as opposed to unreliable.

In the case of Goldman's barn facade county thought experiment, the effect of drawing arbitrary boundaries (in this case, geographical boundaries) becomes apparent, and the metaphor of gerrymandering makes good sense.

How does the metaphor apply to the rule-following argument?

The regularist, dispositionalist reponse to the rule-following argument has a boundary problem as well. Say we try to give a dispositionalist account of a concept like "horse". We say that the concept consists just in my disposition to call certain things horses. But then we have a problem because not all the things I'm disposed to call a horse are actually horses. So how do we rule those cases out? Even if we say that a horse is what I am disposed to call a horse in favorable conditions, there will still be situations in which I call something that isn't a horse a horse. The upshot is that to actually draw the appopriate boundary, it looks like I'm going to have to cheat and bring in the concept horse, which is what I was trying to give a reductive account of.

In both the regularist response to the rule-following argument and in the reliabilist account of knowledge, we want a non-arbitrary way of drawing the relevant boundary that doesn't simply rely on our intuitive grasp of the concept we're trying to get a handle on.

I liked David's explanation of the gerrymandering metaphor, but I had a question about Brandom's "solution" to the gerrymandering problem for the reliabilist. Roughly, his solution to the problem, his way of fixing the relevant boundary, is to rely on the attitudes of subjects--basically, if I have understood him correctly, that we decide what the relevant boundary is:

"What in practice privileges some of the reference classes with respect to which reliability may be assessed over other such reference classes is the attitudes of those who attribute the commitment whose entitlement is in question" (p. 212).

I worried that this wasn't a real solution to the boundary problem, since there is nothing to suggest that the attributers will agree on where the boundary should be drawn. Should the subject's reliability then be attributer-dependent? Maybe, but then whether a subject counts as reliable depends completely on the vagaries of his attributers. It would sure help here to be able to simply say that the boundary should be drawn according to the attitudes of those attributers who correctly assess where the boundary should be, but of course Brandom can't take that route.

The workshop wound down with a debate between Jason and Aidan on the role of experience in observational knowledge, which I'm afraid I can't accurately reproduce here. I'd be happy to add anything to this report that they suggest.

We agreed that instead of reading Brandom's account of action, we would jump ahead to chapter 8 next time, in order to silence once and for all the constant response to any tough questions:

"Wait until chapter 8".

See everyone in two weeks.

1 comment:

Goldman argued that a person's belief that he perceived a real barn would only be accidentally true if he saw the real barn accidentally in a town where

there was only one real barn and 999 other perfectly realistic facades that he would not

have been able to distinguish as fake. I accept this argument, except for the following.

I can imagine a person able to distinguish the real barn. So if the man's assumption is unreliable, isn't it because he could not tell this barn from the facade he knows nothing about? Isn't a stronger example needed? If he is unreliable because of the arrangement of things that allows him to fortuitously avoid a mistake, then that means the example of barns and facades is selected against the possibility that a human could tell the difference. I don't think Brandom would argue that the perceiver's ability, if he had it, to make this distinction would itself take on the role of accident. I think this shows that Goldman's paper has a loose end, not that it is thus proven unsound.

What if the perceiver lives in the "one real world" out of the only 1000 worlds in the universe, 999 of which are worlds where all humans live in complete deception?

This does not seem to me a question about where the boundaries of the objects of knowledge are drawn, but what the conceivable powers of perception are. It is still at least conceivable that there could be a human being not deceivable in this way. So the billions of others who live in the "one real world" are the ones who don't know

their world is real in the sense that this individual knows it.

What, on the other hand, happens if the barn perceiver can

distinguish the real barn from the fake--what if it does not occur

to him that the barn might be a photograph? Does his ability to distinguish it still count even if this does not occur to him? Would his ability be dormant? These questions seem unnoticed by Goldman.

How, again, does that affect "Goldman's Insight" as

Brandom calls it?

Post a Comment